Welcome to Hitting the Books. With less than one in five Americans reading just for fun these days, we've done the hard work for you by scouring the internet for the most interesting, thought provoking books on science and technology we can find and delivering an easily digestible nugget of their stories.

End Times: A Brief Guide to the End of the World

by Bryan Walsh

Grow out your apocalypse beard and strap on your doomsday sandwich board, we're all gonna die! Humanity has always lived on knife edge, our species perpetually one war, one plague, one eruption, one meteor strike away from extinction. But should our species kick the bucket during the 21st century, it may well be through our own actions.

End Times by Bryan Walsh takes an unflinching look at the myriad ways the world might end -- from planet-smashing asteroids and humanity-smothering supervolcanoes to robotic revolutions and hyper-intelligent AIs. In the excerpt below, Walsh examines the work of environmental researcher Klaus Lackner and his efforts to combat climate change by sucking carbon straight from the air.

It might be the German accent, but Klaus Lackner has a way of speaking that lends an air of authority to his statements, even when what he's suggesting seems to be science fiction. "If you asked me fifteen years ago," Lackner told me from his lab in Tempe, Arizona, "I would have said we need to figure out how to stabilize what we're doing to the atmosphere by reducing carbon emissions. Now I'm telling you we're way past that. We have to change carbon levels directly."

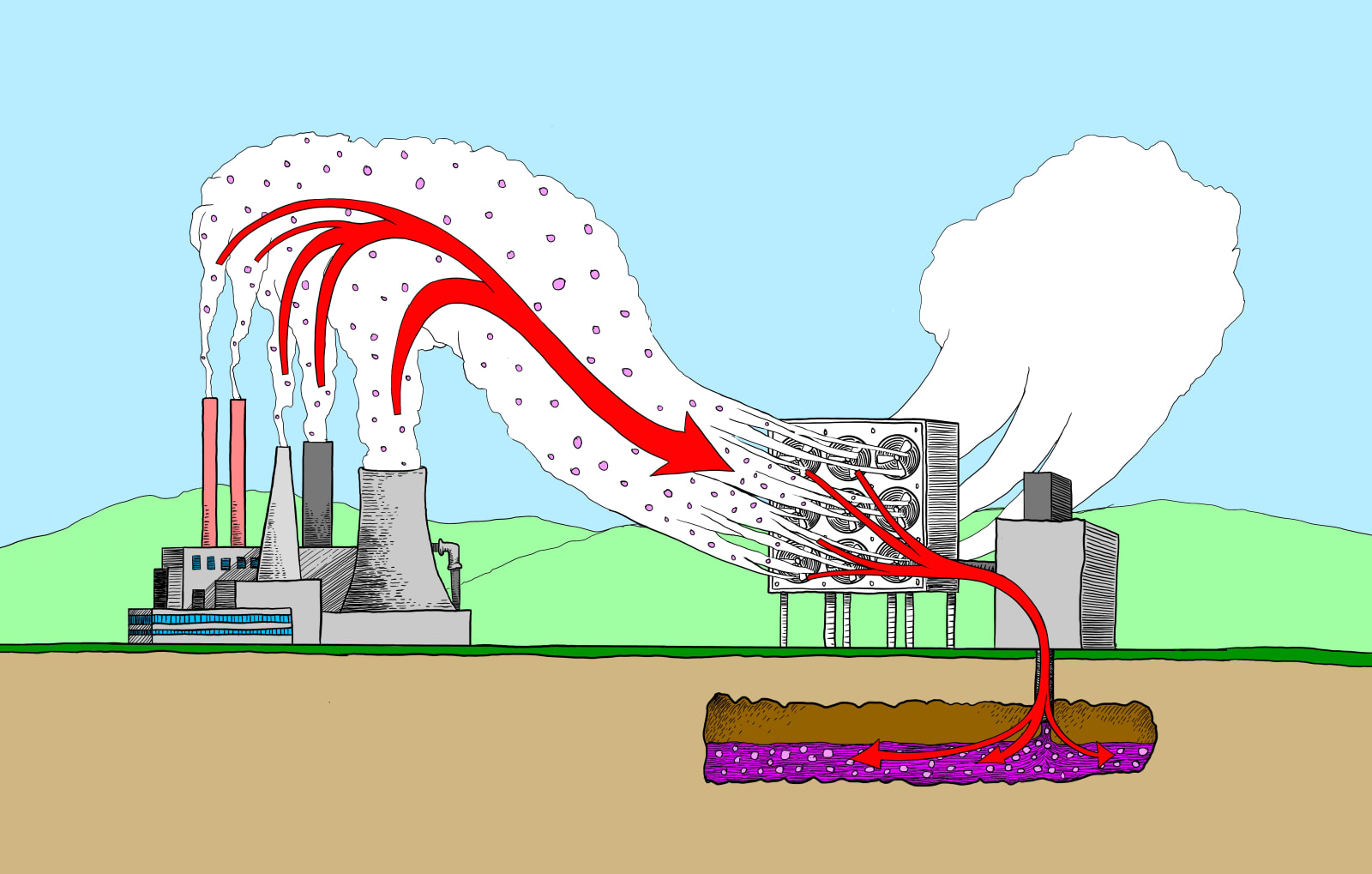

Lackner is the director of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions at Arizona State University and an academic leader what will be one of the most important fields of the future: carbon capture. Lackner is working to build machines capable of capturing and storing carbon dioxide in the air, a process called carbon sequestration. While most climate policy focuses on cutting future carbon emissions by replacing fossil fuel energy consumption with zero-carbon renewables or even nuclear power, Lackner aims to reduce current levels of carbon dioxide directly by sucking the gas out of the air. If it can be done -- and if it can be done affordably -- it would be nothing less than a technological miracle. And as Lackner himself says, we're at the point where we need miracles.

Emissions of greenhouse gases lead to warming because over time they add to the carbon concentration in the atmosphere. During humanity's pre-industrial history -- when the climate was like Little Red Riding Hood's last bowl of porridge, not too cold and not too warm -- carbon levels were around 280 parts per million (ppm). By 2013 they had passed 400 ppm and will only continue to rise. Even if future emissions are vastly reduced, the time lag of man-made climate change means that carbon concentrations will continue to grow for a while, and the climate will continue to warm. But if Lackner's invention works, we could bring carbon levels down, perhaps closer to that original 280 ppm -- even if it proves politically and technologically difficult to reduce carbon emissions from energy consumption.

This would be geoengineering in action -- using technology to manually fine-tune the climate, the way we might adjust the picture quality on a television. And in some form it will be necessary. The UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has considered more than a thousand scenarios for future climate change. Of those, only 116 actually see us keeping warming below the 3.6 F red line -- and of those 116, all but eight require carbon removal, or what's also called negative carbon emissions. That's in part because we've already baked so much future warming into the climate with the carbon we've already emitted, and in part because the fossil fuel habit is so hard to break, especially for those parts of the developing world that depend on rapid economic growth and the energy use that accompanies it. The only way to square that fact with the equally pressing need to keep warming below 3.6 F is to bake in a technology that doesn't yet exist commercially.

In 2011, a team of experts reported that pulling CO2 from the air would cost $600 a ton, which would make the bill for capturing the 37 billion tons of CO2 emitted in 2017 -- one year's worth -- a cool $22 trillion, or more than a quarter of total global GDP. But progress is being made -- in June 2018 a team of scientists from Harvard and the start-up Carbon Engineering published research indicating they might be able to bring that price of capturing a ton of CO2 down to between $94 and $232. That would mean it might cost between $1 and $2.50 to capture the CO2 generated by burning a gallon of gasoline, less than the amount of fuel taxes British drivers currently pay. Lackner believes that if he could get 100 million of his carbon capture machines running, he could reduce carbon levels by 100 ppm, taking us out of the danger zone.

If that price keeps going down -- a big if -- we might be able to save ourselves. And effective and cheap carbon sequestration would have the added effect of sweeping away many of the moral and political conflicts around climate change. If emitting the carbon that causes climate change is a crime, then we are all criminals. But if carbon dioxide is just another form of waste that can be disposed of safely, then we wouldn't feel any worse for emitting carbon than we would for producing our garbage bag full of household trash. Treating carbon emissions as waste to be removed defuses the psychological dissonance that can hinder climate policy -- the guilty gap between all that we know about climate change and the little that we actually do about it.

"I would argue by making carbon emissions a moral issue, by saying that the only way to solve the problem is by donning a hair shirt, you actually invite people to resist you," said Lackner. "They just stop listening to you."

Let's hope that carbon capture becomes a reality, although a recent study in Nature Communications estimated that it could take a quarter of the world's energy supply in 2100 to power enough air carbon capture machines to keep warming below dangerous levels. And that's assuming that carbon capture ever becomes a feasible product -- many would-be world-changing technologies have expired in the valley of death between the lab and the market. We'll need to continue developing low and zero-carbon sources of energy to reduce the risk -- including the existential risk -- that climate change presents.

Yet I believe we have no choice but to move full steam ahead on air carbon capture, for the simple reason that the strategy fits who we are. We are not a species that plans deeply into the future. We are not a species that is eager to put limits on ourselves. We are a species that prefers to stay one step ahead of the disasters of our own making, that is willing to do just enough to keep going. And we are a species that likes to keep going. Carbon capture won't answer the question of what we owe the future, or prove that we've somehow matured. But it will provide an insurance policy against the worst, most catastrophic effects of climate change, that fat-tail risk that could bring extinction in its wake. It will prove we're just smart enough, even if that means we might yet prove too smart for our own good.

Excerpted from End Times: A Brief Guide to the End of the World by Bryan Walsh. Copyright © 2019 by Bryan Walsh. Published by arrangement with Hachette Books.

Tech

via https://www.aiupnow.com

, Khareem Sudlow