NEW YORK, United States — When Steve Madden bought the sneaker start-up Greats in August, it appeared to be the sort of deal every venture capitalist dreams about: a multibillion-dollar conglomerate annexing a risky-but-fast-growing asset, a lucrative exit for the 5-year-old start-up.

But Greats’ investors were hardly the winners of this particular deal. Multiple people familiar with the deal described it as an emergency sale after a failed funding round. The purchase price was less than Greats’ valuation in 2017, the sources said.

Greats and Steve Madden did not respond to requests for comment.

As a generation of digital-native consumer product companies such as Warby Parker and Bonobos enter their second decade, the VC-funded, direct-to-consumer business model they pioneered is facing a reckoning.

Over the last decade, thousands of companies selling everything from shoes to T-shirts to toothpaste have followed the Silicon Valley playbook of aggressively raising capital and pursuing growth at all costs. They cut out middleman retailers and undercut established competitors’ prices. Their investors tolerated years of losses because the goal was scale: secure a big enough share of the market, steer clear of wholesale, drive down unit costs, and profits would follow.

For a while, it worked like a charm, and remade the fashion industry in the process. As the Everlanes of the world stole market share from Gap and J.Crew, they forced these traditional retailers to improve online services and offer consumers livelier, more relevant products.

All this unicorn status, it’s just inflated. It’s paper money and it’s not real.

Direct-to-consumer brands raised round after round of capital at higher and higher valuations. Much of that cash was funnelled toward marketing as it became harder to acquire new customers and Facebook and Google hiked advertising prices.

Many of these companies are now at the point where investors expect an exit: either an initial public offering or an acquisition by a larger retailer. Neither path looks particularly promising at the moment.

Fashion’s IPOs have largely flopped: online luxury marketplace Farfetch has seen its shares plunge more than 65 percent since their September 2018 debut, and even Revolve, which is profitable, is down 55 percent from where it closed on its first day of trading. The high-profile failure of WeWork’s botched IPO has cast fresh doubt on the ability of other money-losing start-ups to go public.

Acquisitions have also been few and far between. Walmart and other large retailers went on a buying spree a few years ago, hoping digital start-ups could help modernise their operations from within. That hasn’t always panned out; Walmart sold Modcloth in October, just two years after acquiring it, and has laid off staff at Bonobos, which it bought in 2017. Its efforts to replicate DTC brands’ success with in-house labels are off to a slow start.

In short, direct-to-consumer companies — and their investors — are trapped.

“All this unicorn status, it’s just inflated. It’s paper money and it’s not real,” said Alex Song, founder of Innovation Department, a digital brand creation platform, and a former private equity associate at Goldman Sachs. “These investors are stuck in ... this moment where they believe that they have a lot of value, but without any path for liquidity.”

And there’s no going back. The DTC boom has had an irrevocable impact on the retail economy as well as consumer culture. It has contributed to the closure of thousands of stores and trained shoppers to expect free shipping, no-questions-asked returns and other expensive conveniences.

But unprofitable DTC companies face some tough choices, whether that means taking on more debt or accepting investors at a lower valuation. Success could now mean spending years improving the bottom line until healthy enough to be sold. Failure to do so could mean selling at a steep discount or closing up shop entirely.

From left: Warby Parker co-founders Neil Blumenthal and Dave Gilboa, Away co-founder Jen Rubio, Forerunner Ventures founder Kirsten Green | Collage by MC Nanda

Nasty Gal, Birchbox and the Honest Company, for instance, all generated nine-figure sales, racked up round after round of venture capital and plenty of glowing media reports. Nasty Gal filed for bankruptcy in 2016, and later sold to Boohoo for $20 million. Birchbox raised nearly $90 million but wound up selling a majority stake to hedge fund Viking Global for $15 million. Jessica Alba’s Honest Company reached a reported $1.7 billion valuation in 2015, but took a down round two years later as sales lagged expectations.

That’s not to say there haven’t been success stories. Reformation recently became profitable and sold a majority stake to private equity firm Permira Partners in July to continue its expansion. Rothy’s, the 3D-knit shoe start-up, achieved profitability soon after its seed funding round. Harry’s sold to consumer products giant Edgewell for $1.37 billion in May, or about four times its revenue, according to Reuters.

But these stories are few and far in between, and even some successful investors say the Silicon Valley playbook may be a poor fit for fashion and other product-driven companies.

“We got lucky with Harry’s because there hasn’t been a tremendous number of exits and even fewer venture-type exits,” said Sean Judge, a principal at Highland Capital Partners, which invested in Harry’s.

“This business model, at this point, has shown itself to not really work,” said Sam Kaplan, a venture partner at Burch Creative Capital, whose portfolio includes Baublebar, Chubbies and Solid & Striped. "Brands are fundamentally different than a software product or a healthcare product."

“Brands need to breathe,” he added. “If people don’t stumble upon it, discover it organically and form that emotional connection with it, then it will die.”

Dangerous Assumptions

Warby Parker wasn’t the first consumer-product company to court Silicon Valley investors, but it is often credited with popularising the idea of a direct-to-consumer play built around a narrowly defined category. It launched online in 2010, opened its first store in Soho in 2013 and by 2018, it was valued at $1.75 billion with more than 60 stores.

There was a period where every DTC company was getting funded, and you had weird categories — toilet paper, towels and condoms.

Since then, the model has spread from suitcases and mattresses to canned water and erectile dysfunction medication. They found champions among investors eager to grab a piece of the e-commerce boom. Near-zero interest rates in the wake of the 2009 recession meant there was plenty of cash sloshing around, looking for a home.

During the early years, the strategy was easy: open an online shop and use venture money to flood Google and social media with ads.

“It was the heyday of super-low CPAs [cost per acquisition],” said Melanie Travis, founder of swimwear brand Andie and the former director of brand experience at BarkBox, a monthly subscription for dog products.

Andie swimwear | Source: @andieswim Instagram

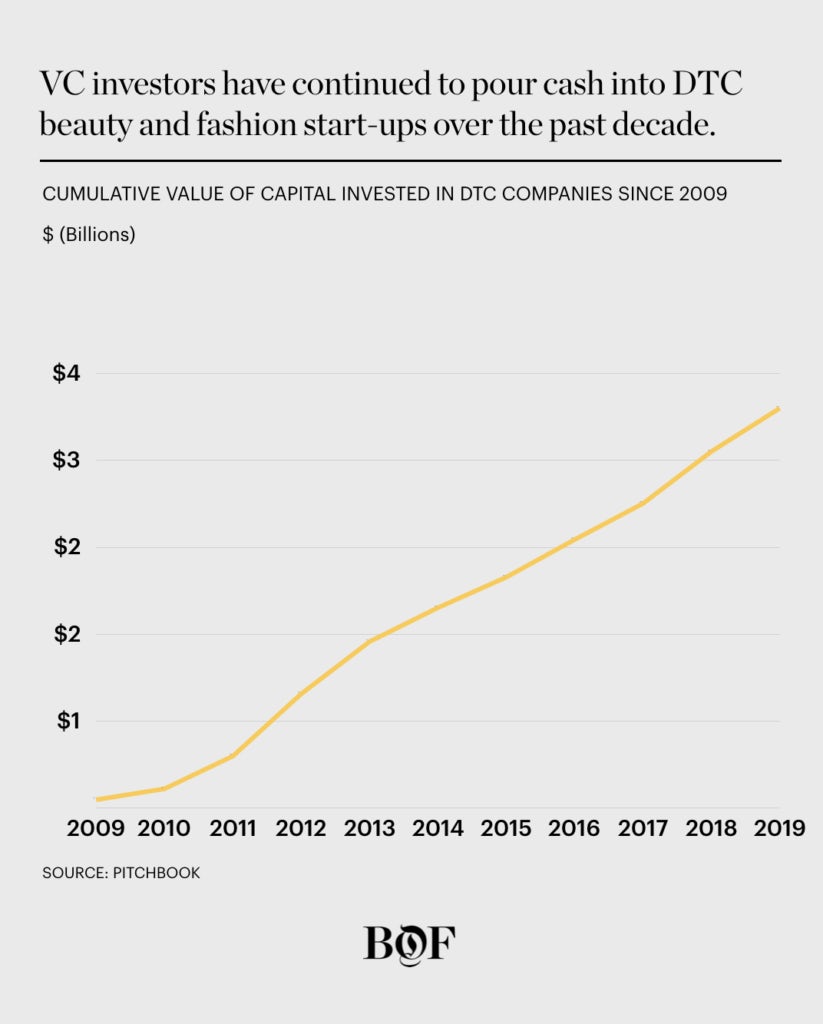

In 2010, there were 32 equity deals in the direct-to-consumer retail space, according to Pitchbook data, which counts venture and private equity fundraise rounds, as well as strategic investments. By 2017, the annual deal count rose up to 196 deals, including Reformation’s $25 million Series B round and Casper’s $170 million Series C, led by Target. Last year, there were 173 deals, and there were 104 this year through August.

“There was a period where every DTC company was getting funded, and you had weird categories — toilet paper, towels and condoms,” said David Goldberg, General Partner at Corigin Ventures, a venture capital firm based in New York. “Those who weren’t in this space had FOMO to get in.”

With so many brands advertising on the same channels, attempting to reach the same customers, costs quickly began to rise. Many start-ups pivoted; MM.LaFleur and Allbirds use print catalogues to acquire new customers, StockX advertises on television. Untuckit found in-flight magazines a surprising route to new customers.

Many others have found themselves trapped in what Song calls the “vortex of venture capital,” where the more money a company raises, the more money it needs to raise. As investors pour money into a brand, they expect returns that are often achievable only by increased marketing. That spending in turn requires finding more investors, who have expectations of their own.

In theory, a brand can break out of this cycle as customers return to make additional purchases. But where a user might find Amazon Web Services too useful to drop — or find migrating to a rival inconvenient — consumer products aren’t as sticky. Bonobos may pitch itself as having engineered the perfect pair of pants, but to most customers, pants are pants.

“These companies are funded like a tech company assuming that once you have a customer they’ll stay with you,” said Pat Robinson, Managing Director at CircleUp Growth Partners, an equity fund and credit provider. “We’re starting to see kind of a world where brands ... forget that they’re consumer product companies and see themselves as digital marketing companies ... We’ve seen a bit of boom or bust.”

As marketing costs rise, so does competition, counterfeits and knockoffs. Allbirds, for one, saw copycats within a year after launching in 2016, co-founder Joey Zwillinger told BoF in August. Even Amazon released its version of Allbirds-inspired minimalist speakers in September.

“You can try out one brand today and another tomorrow, and no one is owning these customers as much as they thought they would,” Goldberg said.

More Money, More Problems

Many investors who spoke with BoF said the typical goal is for a 30 percent profit across an entire portfolio of assets, each of which are held for an average three to eight years. For tech investors, this is attainable because if one successfully scaled technology platform can yield returns of 10 times their initial investment, it offsets losses on other failed investments.

For product-driven companies, however, multiples tend to be lower because the cost of holding inventory makes scaling a slower and more expensive proposition. Rather than a 1,000 percent ROI, a realistic success story would hover around 300 percent.

Bonobos, for instance, sold to Walmart in 2016 for $310 million after raising $128 million. According to a person familiar with the matter, the transaction provided a 2.7x return to its Series A investors — a bit of an anticlimax for what had been one of the hottest DTC brands.

That deal looks better and better as time passes. Many start-ups will struggle to find buyers at their current valuations. If revenue growth slows and a company has yet to turn a profit, it’s tell-tale sign that “you’ve built a business that’s addicted to capital,” Song said. “And a strategic acquirer does not want a business that’s addicted to cash.”

Raising too much cash also warps the natural trajectory of a company.

Brands that build awareness and loyalty over the long term have a better shot at survival than those pursuing the quick rush of Instagram-generated sales, said Kearnon O'Molony, co-founder of Cuup, a lingerie start-up backed by Forerunner Ventures and Global Founders Council.

By contrast, customers who stumble upon a brand through word-of-mouth and other “organic” marketing are cheaper — or even free — to acquire.

Cuup bra | Source: @CUUP Instagram

“If you take in money quickly and need to generate growth quickly, [your strategy] tips over to paid acquisition only because you’re not allowing time that’s needed to benefit from word-of-mouth marketing or earned media,” said Eric Fisch, head of retail and apparel banking at HSBC.

Raising too much cash can hide the fact that some products simply don’t need to exist. Look no farther than the bevy of swimwear or underwear start-ups that emerged in recent years, or the infamous Juicero — the $400 Wi-Fi connected juicer that raised nearly $120 million only to implode when users realised that its juice packets can just as well be squeezed by hand.

“Most of these companies haven’t really innovated, they’ve just created novelty,” said Song. “It's very much saying, ‘Hey, let's make something more beautiful, something that speaks more clearly to a millennial demographic and feels attractive and digestible. And we'll see what happens from there.'”

No Exit

Nothing is more indicative of the troubles facing the direct-to-consumer model than the dearth of recent exits in the space.

“There was so much excitement from the investors’ perspective that things may have been overvalued earlier,” said Highland Partners’ Judge.

Entrepreneurs, investors and deal makers entered 2019 with high hopes for strategic acquisitions.

“I closed three deals last year, and this year it could be anywhere from five to six,” one retail investment banker told BoF in January. “As long as market conditions hold up … I’m expecting to see a lot of activity.”

But few have come to fruition.

Unicorns like Casper, Warby Parker and Glossier would be expensive for retailers to acquire. Going public is a less-appealing option.

“What’s happened with WeWork, Uber and Peloton — they all tanked after IPOing,” said Andie’s Travis. “This means that if you’re a lossmaker, IPO isn’t an option because the public market investors have shown that they don’t want that.”

It’s a buyer’s market, according to Siddharth Hariharan, Managing Director at investment banking firm Rothschild & Co. Fashion and accessories companies are specifically harder to sell right now, he added, as shareholders aren’t convinced of the strength of the category.

For some, the only option is to focus on profitability instead of growth. But in a culture that values top-line growth above all else, managing the bottom line can be painful and require cutting fixed costs like staffing and stores, or considering wholesale. For a number of insolvent businesses, it may be too late. Under new owner Go Global, Modcloth has laid off a portion of its staff, Jezebel reported last month.

“People really underestimated the costs of running an e-commerce operation, whether that’s staff or equipment and then the variable costs like server space,” said Kaplan. “Customer acquisition cost was the last barrier that I think people just didn't didn't see coming.”

As for other DTC players today, competition will stiffen.

if you’re a lossmaker, IPO isn’t an option because the public market investors have shown that they don’t want that.

“All the new players are trying to keep up with the changing demands of consumers and the incumbents are trying to as well,” said Tina Sharkey, founder of Brandless, a DTC product company. “Now everyone is trying to meet them all at once, and only the best will survive.”

Brandless has lost customers since Softbank invested $240 million last year, The Information reported in June. The company, which initially sold merchandise priced under $3, now offers higher-priced items and has recently made a push into selling CBD products.

Meanwhile, some DTC giants maintain that not every start-up faces investor pressure to sell.

“There definitely investors out there who push for an exit but we chose investors who want to see us expand out to new markets,” said Jen Rubio, co-founder of Away, which counts institutional investors like Wellington Management Co. among its backers. “You can’t build a true, long-lasting brand based on paid marketing alone.”

It’s Still a DTC World

A new generation of digital companies are learning from their predecessors’ problems. Some new start-ups have been more conservative in raising money and focused on building a sustainable business over a fast-growing one.

You raise the next round, and you're on that treadmill. At any point along the way you could fall off.

Online shoe brand Thursday Boots Company, founded in 2014, did not take outside capital until it sold a minority stake to a private equity firm in 2017, by which point it was already profitable.

“We didn't do the traditional VC playbook, which was, you raise a lot of money in a big round, you put that money into growth, marketing, and at the next milestone, you raise the next round, and you're on that treadmill,” said founder Connor Wilson. “At any point along the way you could fall off … We've benefited from being able to see this first generation of direct consumer brands, and seeing some of the mistakes they’ve made.”

Thursday boots | Source: @thursdayboots Instagram

Wilson added that when he and his partners were building the initial business model, they used an equation that assumed that customers never buy a second pair of shoes. This way, they could focus on building the product and ensure positive margins from day one.

Song’s rule of thumb is to stop the fundraising after Series A to focus instead on paving a path to profitability.

Cuup’s founders, for instance, already know that their goal is to not have to raise a Series B round. Travis said she knows that Andie will also be conservative in raising capital.

“We’re not going to raise $100 million to sell swimsuits on the internet,” she told BoF.

As DTC brands mature, so does the channel itself. After years of selling direct online, some companies are finding that expanding into wholesale, once anathema to many digital-first start-ups, is the next step to creating cash flow.

“It’s not that direct-to-consumer business as a channel is dying, it’s that direct-to-consumer is and always has been a distribution channel alongside wholesale and owned retail,” said Kaplan of Burch Creative Capital.

On, a Swiss running sneaker brand that never took on VC money, sold both direct and via wholesale since its 2010 founding.

“The expertise of retailers is necessary for consumers, especially in the performance category,” said Chief Executive David Allemann. “We have 5,000 doors which means that if 20 people per day in each store touch our products, that’s 100,000 contacts. Comparing that to digital acquisition, if you’re paying for 100,000 clickthroughs and it costs $3 per click through — that’s $300,000 per day.”

Another option is for start-ups to consolidate under holding companies, said HSBC’s Fisch. Design agency Gin Lane, for instance, was the premier DTC branding company, having worked with the likes of Harry’s and Sweetgreen. Earlier this year, it ditched design entirely to become Pattern, a DTC conglomerate that will be the parent company of up to five new digital brands.

“It makes sense for them to combine all of these costs: platforms, supply chains, customer service, all of this is getting more expensive,” Fisch said.

Some companies are also pitching themselves as platforms to launch new brands or expand into new product categories, to show their model is scalable and can be replicated. Glossier launched a sub-brand, Play, earlier this year, for instance.

“If you look at the brands with valuations above $1 billion, we’re building something that’s much bigger than what we are today,” said Away’s Rubio. “We’re bigger than just luggage. [Glossier’s] Emily Weiss has talked about how she’s building a beauty empire and Allbirds have talked about how they're a sustainable materials company, not just shoes.”

Whatever happens to today’s crop of digital brands, the onslaught of direct-to-consumer companies has irrevocably changed the nature of retail. It’s pushed incumbents to adapt — and those that didn’t are perishing. It’s the reason why major players are developing their own in-house brands that mimic DTC competitors, like Walmart’s Casper copycat, Allswell, or Target’s private-label lines.

“Direct-to-consumer brands speak their own language and tell their stories to the fullest,” said Marshal Cohen, chief industry adviser of retail at the NPD Group. “Almost every big-name retailer has come up with something to elevate their game and they’ve been forced to do this because of direct-to-consumer and third-party retail are raising the bar — for better or for worse.”

The reckoning of the direct-to-consumer channel doesn’t mean there isn’t a place for venture capital; there will always be innovative, category-pushing concepts that need funding to get started, said Forerunner Ventures founder Kirsten Green.

Five years ago, these innovative companies were often brands with a creative spin on consumer products. That market is now saturated, and innovation in 2019 may be less about products and more about services or platforms, Green said. One of her latest investments, for instance, is an artificial intelligence-powered brand recommendation app created by Stitch Fix alum Julie Bornstein.

“There will always be an opportunity to start a company with a marginally better product,” Green told BoF. “I just don’t know if a lot of these companies today need venture capital.”

Related Articles:

How Online Brands Can Pave a Path to Profitability

Startups

via https://aiupnow.com

Cathaleen Chen, Khareem Sudlow