LANDRIANO, Italy — In August, the roof fell in on Yoox Net-a-Porter Group.

Near the beginning of the month, a summer storm hit the Richemont-owned fashion e-commerce leader’s new logistics hub in Landriano, Italy, a municipality about 40 minutes from the centre of Milan. It damaged the building so badly that the warehouse, where most of the work is automated, was out of operation for several weeks, according to multiple sources, who said employees were encouraged to keep communication about the incident off email to stop the news from spreading.

The warehouse snafu was the latest in a series of mishaps stemming from a troubled technology and logistics overhaul at the group — known as YNAP — that began more than three years ago and has cost hundreds of millions of euros.

The project was ambitious in both scale and scope, but the full extent of the troubles at the luxury e-commerce platform, which Richemont fully acquired in May 2018, was not made clear until mid-May 2019, when Richemont announced its financial results for the previous fiscal year. The Swiss conglomerate — which also owns Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels and Chloé among other brands — reported its weakest profit margin in more than a decade, taking analysts by surprise.

Richemont’s “Online Distributors” unit — made up of YNAP and secondhand-timepiece seller Watchfinder — delivered double-digit sales growth for the year ending March 31. The company also reported a €264 million operating loss (around $291.7 million at current exchange rates), including a €165 million ($182.3 million) write-down of the value of its YNAP acquisition.

The remainder of the losses were pegged to growing costs stemming from a global technology and logistics platform migration at YNAP, estimated at €200 million ($221 million) for the fiscal 2019 year alone, lowering Richemont’s operating margin for the year from 16.7 percent in 2018 to 13.9 percent.

Richemont continues to lose money on YNAP. In the 2020 fiscal year’s first-half results, reported on November 8, the division’s sales were up 32 percent to €1.2 billion ($1.3 billion), but losses widened to €194 million ($214 million), or a negative 16.5 percent operating margin. (A year earlier, losses were €115 million ($127 million), or 13 percent.)

The upgrade, part of a wider transformation meant to future-proof YNAP in the face of growing competition, had the opposite effect.

The scale of the ongoing investment in multi-brand e-commerce is a cause for concern for some analysts. René Weber, an analyst at Bank Vontobel, called the operating losses at Richemont’s online distributors division “disappointing,” in a Bloomberg report last summer.

While Citi analyst Thomas Chauvet more recently said he believed investing in the long term was good for Richemont's future, he was concerned about the group’s losses not only at YNAP, but also in its watch division, maintaining a “neutral” rating on the stock. “Richemont is effectively loss-making on 30 percent of group revenues,” he told Reuters.

Today, BoF can reveal some of the underlying causes of these losses, after an investigation conducted over several months.

The reporting uncovered evidence suggesting that the upgrade, part of a wider transformation meant to future-proof the company in the face of growing competition, had the opposite effect. Rather than becoming the internet’s luxury e-commerce hub, YNAP is beset by competition on all sides and missing its target of €4 billion ($4.4 billion) in sales by 2020, sucking up cash at Richemont at a time when the conglomerate’s rivals are busy expanding.

Richemont’s online challenges can be traced back to a strategic roadmap, “Fast Forward to 2020,” presented by YNAP executives at the then-independent group’s first annual shareholder meeting as a public company in July 2016. The plan, which made generous use of corporate jargon like “cross-fertilisation” and “unlocking synergies,” promised to double sales to about €4 billion ($4.4 billion) in roughly five years. To get there, executives proposed developing a single technology platform that would be shared across YNAP’s subsidiaries, which included Yoox, Net-a-Porter, Mr Porter and The Outnet, as well as building a tech hub in London and the Landriano warehouse.

Even prior to this, Johann Rupert, chairman of Richemont — which held a controlling stake in the Net-a-Porter Group before the merger with Yoox and a 50 percent share of the merged company in 2015 — was extolling the virtues of such a platform, which he hoped to open up to the entire luxury goods industry.

It’s too big a game for any company to try to dominate.

“Yoox on its own, Net-a-Porter on its own, Richemont on its own — and I said to [LVMH Chairman and Chief Executive Bernard] Arnault the other day, ‘Forget it!’ — LVMH on its own. We’re not big enough,” he said at the 2015 Financial Times Business of Luxury Summit. “I was speaking to him, as I’ve spoken to Kering, about joining us on that platform, to make it totally neutral. It’s too big a game for any company to try to dominate.”

LVMH has yet to take Rupert up on his offer. Kering, which for many years used Yoox technology to power several of its brand e-commerce sites, has since decided to take those operations in-house.

As the YNAP upgrades continue, sources close to the operations suggest that the company will end up spending far more than the €500 million ($552 million) it originally budgeted for the project, or risk losing further ground to rivals. A YNAP spokesperson declined to comment on this, or any other point or query put forth by BoF over the course of several months. Richemont also declined to comment.

At a shareholder meeting on May 17, Richemont Chief Executive Jérôme Lambert and Chief Financial Officer Burkhart Grund did address the significant technology costs at its Online Distributors unit and the revenue drop at The Outnet, the first YNAP site to migrate to the new platform. Grund called their learning curve “steep and painful,” but the two executives appeared confident in the future of YNAP’s five-year plan.

“Being a tech business, you know, [capital expenditure] tends to be higher in periods of intense work around re-platforming,” Grund said. “I think we should stay at that level for a while, probably two-to-three years into the future, and then if we do things well, that should start to level off or decline as a percentage of sales.”

But how did YNAP go from trumpeting a tech and logistics transformation to a situation where senior executives at its parent company had to stand before investors and explain unforeseen technology costs?

The merger and Richemont’s later acquisition of the whole group were pushed by Rupert’s belief in the single shared technology platform.

YNAP’s pillar businesses are Net-a-Porter, which sells women’s fashion, and Yoox, which stocks off-season merchandise. Both were founded in 2000 and have dominated the fast-growing luxury e-commerce market for nearly two decades. The two companies merged in 2015 to form a supergroup, with Yoox Founder Federico Marchetti installed as chief executive. Net-a-Porter Founder Natalie Massenet did not support the deal and exited the company soon after.

Richemont maintained its stake in YNAP while it was a public company, acquiring it for €2.7 billion ($2.9 billion) in 2018. In 2017, YNAP’s last full year as a public company, the group generated €2.1 billion ($2.3 billion) in net sales, including a business providing white-label technology to luxury brands like Valentino and Marni, which contributed about 10 percent of revenue.

Both the merger and Richemont’s later acquisition of the whole group were pushed, at least in part, by Rupert’s belief in this single shared technology platform.

When the “Fast Forward to 2020” initiative was announced in 2016, YNAP publicly committed to an implementation timeline — both Mr Porter and Net-a-Porter were supposed to complete their migrations to the new platform by the end of 2019. Marchetti also brought on IBM as a partner in a decision made prior to the merger, over the objections of executives at Net-a-Porter. YNAP Global Chief Operating Officer Alberto Grignolo and Chief Technology Officer Alex Alexander, a former Asda executive hired for his understanding of IBM’s software, were tasked with leading the transformation.

The project was slated to involve tapping artificial intelligence technology developed by IBM that would, in theory, allow YNAP to improve its customer experience, helping to maintain the group’s dominance in a fast-growing market increasingly crowded with well-financed competitors, including Farfetch and MatchesFashion. (LVMH would eventually enter the game itself with 24S, its own multi-brand e-commerce site which thus far appears to have failed to scale into a meaningful player.) In 2016, the luxury e-commerce market was worth €19 billion ($20.9 billion) — or 8 percent of total luxury sales — according to Bain & Company. Just two years later, that number hit €27 billion ($29.8 billion), or 10 percent of total sales.

Less than a year into the initiative, 'Fast Forward to 2020' was already behind schedule.

Regular technology upgrades are a necessity for e-commerce businesses in a fast-moving market, but they can often cause significant financial and operational headaches. Recently, fast-growing fashion rental site Rent the Runway had to temporarily stop taking new customers after problems with a software upgrade that made it difficult to easily manage inventory and keep the supply chain moving.

What set YNAP’s project apart was the sheer scale of its ambition.

But by the first half of 2017, less than a year into the initiative, “Fast Forward to 2020” was already behind schedule, according to sources and internal documents seen by BoF.

The Outnet was scheduled to migrate to the platform in the fourth quarter of 2017, just before the busy holiday shopping season kicked into high gear. But the team there voiced concerns with the plan. Senior-level members from each division at the off-price site — technology, merchandising, finance and sales — put together a report detailing the many potential problems they believed could result from the move. In May 2017, they presented this report to senior leadership at YNAP, urging the company to scale back the project or risk a major loss in sales. The consequences of continuing, executives worried, would include not only a short-term revenue drop, but also a poor customer experience that could have longer-term effects on sales.

The problem, the executives outlined, was that the new platform made it difficult for shoppers to easily navigate the site and perform basic functions as simple as returning an item for store credit.

The new platform made it difficult for shoppers to easily navigate the site and perform basic functions like returning an item for store credit.

Their concerns were acknowledged, according to multiple senior-level sources, but the re-platforming project continued as planned.

In order to go live as scheduled, YNAP had to put The Outnet’s front-end onto the old Yoox platform — called F31 — in what one non-technical executive called a “Frankenstein” solution. It was like “fitting a square peg in a round hole,” the executive said. The decision resulted in the departure of several members of The Outnet's technical team.

All the while, YNAP continued to roll out its wider technology transformation, launching what it called a “state of the art” hub in West London in June 2017; a 70,000 square-foot space where a staff of more than 500 people would work on developing IBM-powered artificial intelligence tools — focused on personalisation and image-recognition — and continue to refine the company’s mobile technology, which Marchetti saw as central to the vision. The group talked about creating “disruptive” products for an “unparalleled customer experience.”

That summer, YNAP became the target of short-sellers — or investors betting against the company — concerned about growing competition both from online giants like Amazon and established luxury brands and retailers honing their digital strategies. In order to combat this, YNAP moved up Net-a-Porter’s markdown period in some regions so that the natural bump in sales would be reflected in the second quarter results instead of the third, according to a source.

In September 2017, as The Outnet was about to go live on the F31 platform, the risks associated with the move became very real. According to an internal report delivered to executives that month, The Outnet’s new e-commerce site would lack basic retail e-commerce functionality that was available on the previous incarnation of the site. Customers would not be able to redeem gift cards, exchange items, return items for store credit, create wish lists or view their full order history. There would be no same-day delivery for UK customers, no product recommendations, no product videos and no ability to run private sales. As with other queries, YNAP declined to comment on this.

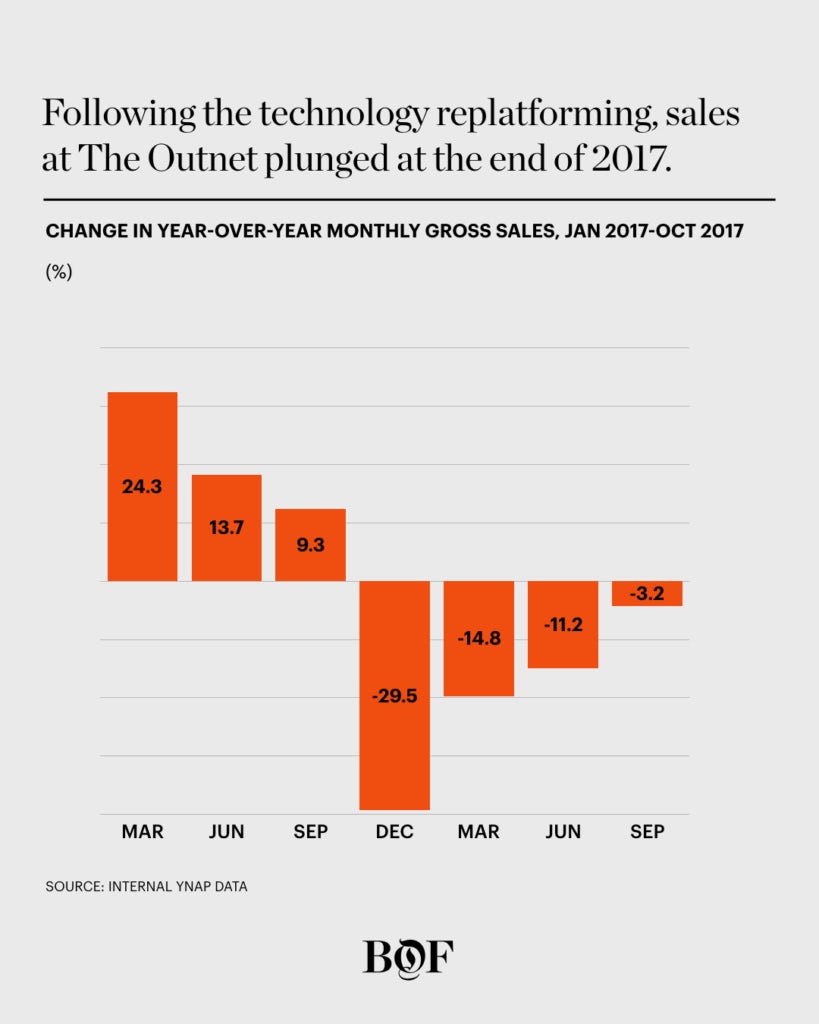

For 12 months after the launch, The Outnet saw year-over-year sales decline every month, according to internal documents viewed by BoF. In September 2017, gross sales at The Outnet averaged €1.1 million ($1.2 million) a day. In October 2017, the month the changeover happened, sales averaged €941,735 (around $1.04 million) a day, down 16 percent from a year earlier. In November 2017, the first full month after the change, average daily sales were €610,277 ($674,440), down 53 percent from a year earlier.

That same November, gross revenue at The Outnet was €18 million ($19.8 million), down more than 50 percent from €39 million ($43.1 million) in November 2016. In December 2017, The Outnet generated €19 million ($20.9 million) in gross revenue, down from €27 million ($29.8 million) in December 2016.

During this period, some consumers took to message boards to complain about the new site. “I don't know how and why, but now it works more terrible than it used to be,” one New York-based shopper wrote on Complaintsboard.com in December 2017. “Now it's absolutely uncomfortable to use it… I don't understand what was the point of this nonsense.” Once again, a spokesperson for YNAP declined to comment on this matter.

While the customer experience was, to some, sub-optimal, logistics was at the heart of the sales drop. One of the major features of YNAP’s re-platforming strategy was its “omni-stock solution,” which entailed moving inventory to Italy as part of a new “hub and spoke” logistics model, which typically involves one central product “hub” supported by smaller, local distribution centres. (At the Net-a-Porter Group, there had long been warehouses in both the US and UK to cover each continent.)

In a 2016 public presentation outlining the plan, YNAP said that the new model — which included the opening of the Landriano facility — would improve operational efficiencies and geographical scalability, shorten delivery times and minimise inventory risk.

When The Outnet launched, the Landriano warehouse was not yet up and running, so products were moved to YNAP’s warehouse in Interporto, Italy, about two hours away. In November 2017, Marchetti acknowledged in a call with investors that the transfer of product caused a sales dip, but did not get into specifics. “We just had a very small bump in the road... it happens, just like when you move houses,” he said.

Doubling down on YNAP could help to further digitise Richemont's overall business, or so the logic went.

Yoox Net-a-Porter Group reported a 16.9 percent increase in sales in 2017, just missing market guidance of 17-20 percent. The Outnet’s sales dive was offset by swift sales at Net-a-Porter and Mr Porter, which had yet to migrate to the group’s new technology platform.

When C-suite executives presented the 2018 budget to the Richemont board, they projected a 21 percent increase in net sales in the off-price channel for the coming year, according to a document.

In January 2018, Richemont made a tender offer to take full control of YNAP for €2.7 billion ($2.9 billion), or €38 ($41.9) per share, an almost 26 percent premium over YNAP's closing price on the Borsa Italiana in Milan that day, valuing the e-commerce group at over €5 billion. Already the company’s largest shareholder, Richemont’s move to acquire YNAP signalled to the public markets that the conglomerate was serious about modernising its digital strategy. The group’s expertise is in hard luxury goods, a sector that offers high margins but has been slow to adapt to the rise of e-commerce. Doubling down on YNAP could help to further digitise the overall business, or so the logic went.

“We are very pleased with the results achieved by Yoox Net-a-Porter Group's management team,” Rupert said at the time. “We intend to support them going forward to execute their strategy and further accelerate the growth of the business."

But between February 2018 and April 2018, sales at The Outnet continued to drop, down between 15 and 30 percent a month compared to the year earlier. On May 10, YNAP was delisted from the public market, with Richemont officially snapping up the shares and cementing the deal. Four days later, when YNAP reported results for the first quarter of fiscal 2018, the company blamed a decline in sales growth in the off-season business on the impact of a pricing strategy designed to mitigate currency headwinds at Yoox and a decreased customer retention rate due to low product availability at The Outnet in the fourth quarter.

The re-platforming has sparked complaints from senior executives of mismanagement and scapegoating, which sources say has eroded morale.

Inside YNAP, however, the ongoing upgrade to the company’s new technology platform has sparked complaints from senior executives of mismanagement and scapegoating, which sources close to the company say has eroded morale. In September 2018, the company had to extend its credit line with an outside lender in order to make payroll, according to a source. (YNAP did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding this.)

There were also concerns among some long-time executives, according to sources, over the value of stock options due to vest this year, which Richemont was not obliged to award if YNAP underperformed. Marchetti and 12 other senior executives, including since departed-Chief Financial and Corporate Officer Enrico Cavatorta, current Net-a-Porter President Alison Loehnis and longtime executive Irene Boni, received shares in Richemont at the time of the acquisition, according to a public document.

Meanwhile, there has been a talent exodus within the group. In the past three years, at least 20 senior executives — C-suite or director-level — have left, including Yoox veteran Grignolo, who then returned as a strategic advisor; Alexander, the IBM expert; and Alessandra Rossi, president of off-season during the time of the tech migration at The Outnet. Many of their direct reports have departed as well. More recently, Toby Bateman, long-time managing director of Mr Porter, quietly departed. (YNAP did not respond to a request for comment at the time of Bateman’s departure.)

Richemont continued to express its support for the omni-stock model during its May 17 shareholder meeting.

In the past three years, at least 20 of YNAP's senior executives have left. Many of their direct reports have departed as well.

“Omni-stock means that you’re selling the stock you purchase, but also… if you don’t have the stock available, that you can leverage the stock of your partner,” Grund said. Later, on a call with investors, Grund added that approximately €200 million ($221 million) of Richemont’s 2019 fiscal year capital expenditures, which increased “a good €300 million over [the] last year,” were directly attributed to technology and logistics spending. “Two-thirds was driven by YNAP, so that’s tech and logistics,” he said.

Grund, however, was confident that these investments would prove to be worthwhile despite initial losses at The Outnet. In October 2018, the site’s sales began growing again, thanks to an improvement in available stock, customer features and increased spending on customer acquisition. (Gross sales that month were €37 million ($40.8 million), up from €29 million ($32 million) in 2017 and €35 million ($38.6 million) in 2016.)

“It's gone down, and then it come back very strongly, after we have fixed the migration, these glitches on the tech side,” Grund said. “Once it was fixed… the sales came very strongly back and have normalised and reached growth rates that we are quite proud of or we should be quite proud of.”

The Richemont executive team was also positive about the migration of Mr Porter to the new platform, which had been completed in one “smaller European market and has done very, very well,” according to Grund.

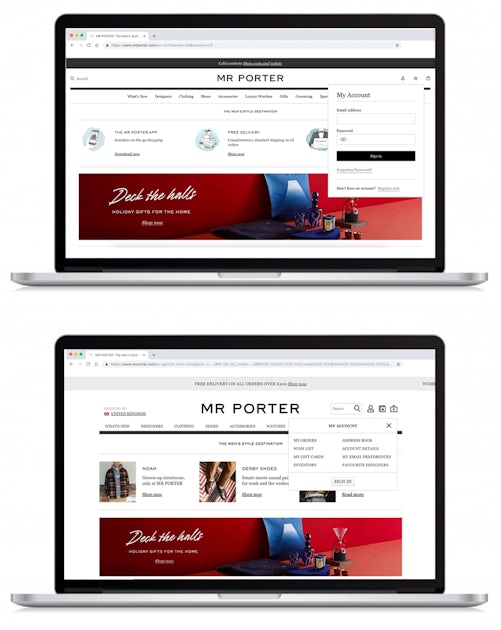

The US and UK Mr Porter websites | Image: Zoe Suen for BoF

The rest of the Mr Porter migration was slated to be completed by the end of the summer or early autumn, the company said. The migration of the US site, a large market for the retailer, did happen. But more recently, the migration of the Great Britain website was halted until 2020 due to a missing functionality, according to a person familiar with the plan. At present, the ability to reserve products for high-spending customers is not possible. As a major driver of sales, the company has chosen to wait until that feature is available.

Net-a-Porter is also slated to begin migration in 2020, behind the schedule that was originally proposed in July 2016.

Back then, YNAP’s goal was to double sales in less than five years, hitting €4 billion ($4.4 billion) by 2020. In the 2018 fiscal year, Richemont reported that its online distribution division, which includes YNAP and Watchfinder, generated €2.1 billion ($2.3 billion). (This number accounted for 11 months of sales at YNAP and 10 months of sales at Watchfinder.) It is virtually impossible that YNAP will reach its revenue target within the next year and a half, despite strong growth overall.

Many of YNAP’s core competitors have faced turbulence, too. At luxury marketplace Farfetch, sales were $602 million in its 2018 fiscal year, up 56 percent from $386 million in 2017. But after an initially warm welcome by the public market, Farfetch stock fell more than 40 percent following the announcement that the company, which remains unprofitable, was acquiring New Guards Group in a $675 million cash-and-stock transaction aimed at turning the fashion e-commerce player into a platform for launching its own brands. In Farfetch’s most recent quarter, year-over-year sales were up 90 percent and losses narrowed, with the company eying profitability by 2021, although analysts have predicted that the company will need to raise more cash by the end of the year in order to keep fuelling growth.

Another formidable opponent, MatchesFashion, has gained market share in recent years, with sales reaching £372 million ($480 million) in the fiscal year ending January 31, 2019, up 27 percent from £293 million ($378 million) a year earlier, when year-over-year sales increased 44 percent. (The 2017 acquisition of MatchesFashion by private equity firm Apax reportedly valued the site at $1 billion.)

Many of YNAP’s core competitors have faced turbulence, too.

However, while MatchesFashion's sales were still growing in the double digits last year — albeit at a slower pace — spending increased dramatically, resulting in an 89 percent decline in operating profit to £2.4 million ($3.09 million). In August 2019, Chief Executive Ulric Jerome unexpectedly exited the company.

Legacy players like Neiman Marcus are also suffering. Most recently, Barneys New York filed for bankruptcy. Its new owner, Authentic Brands Group, is in the process of liquidating its merchandise.

And while consolidation may be on the way, Rupert’s vision, which in 2015 may have been deemed ahead of its time, may never materialise. Each multi-brand player faces unique challenges, but they share one thing in common: growing competition from luxury brands, which are investing more heavily in their own digital sales channels, making it increasingly difficult for any single platform to acquire, and retain, customers.

“Mega-brands — who dominate the luxury industry today — have little to gain long-term from feeding ‘winner-takes-all’ third-party distribution platforms,” Bernstein analyst Luca Solca wrote in a recent note about Farfetch. “We see a risk for Farfetch to grow more moderately, as luxury players wake up to reality,” he continued. The same could be said of its arch-rival YNAP.

For now, though, multi-brand retailers remain the dominant force in luxury e-commerce. Since the closing of the Richemont acquisition, YNAP's combined businesses have continued to grow as promotional periods and discounting have increased.

Mega-brands have little to gain long-term from feeding ‘winner-takes-all’ third-party distribution platforms.

It will require extraordinary execution — and creativity — for YNAP to maintain its position as market leader, however. What made both Yoox and Net-a-Porter so revolutionary 20 years ago was that they transformed the shopping experience. Now, the industry is once again at an impasse that will not be weathered by simply sharpening its current tools, but by having the imagination to anticipate what’s next.

YNAP’s owner, Richemont, may have the cash to further invest in technology, but it’s an expensive strategic path, especially as competitors encroach on the group’s dominance in hard luxury. (Recently, LVMH placed a $14.5 billion bid to buy Tiffany, which would increase its cash flow and strengthen its holdings in the sector.) Richemont is also reckoning with its fashion business, which has struggled to compete against Kering and LVMH’s further-developed retail network and marketing prowess.

And yet, YNAP still represents a growth opportunity. In particular, its joint-venture with Chinese e-commerce leader Alibaba could open up an entirely new customer base if executed properly. In August, there were reports that the group had hired former Unilever executive Yating Wu to be chief executive of the joint venture, now called Feng Mao. But when it officially launched in October, Wu’s name was nowhere to be found on the press release, although a source says she is still with the company. Marchetti, who remains YNAP’s chairman and chief executive, called the partnership “game-changing.”

Related Articles:

Online Luxury's Biggest Players Are Struggling, Too

Farfetch Sees Path to Profitability — in 2021

Startups

via https://aiupnow.com

Lauren Sherman, Khareem Sudlow