Before the network, there is the job.

In the case of Visa, or, to be more exact, the Bank Americard that would eventually be spun out and renamed Visa, the job for consumers was obvious: instant credit for anything, without the need for a merchant-specific account or a visit to the bank for a personal loan. And so, when Bank of America dropped 60,000 Bank Americards on its customers in Fresno, California, in 1958, they had an immediate reason to give this new-fangled financial product a try.

What may be less obvious is why Fresno’s merchants might have been interested, particularly since Bank of America planned to charge them 6% of sales. Remember, this is before the network: it was not at all obvious, as it is today, that the increase in sales enabled by the convenience of credit cards would more than make up for credit cards’ attendant fees. However, it turned out that for small merchants in particular there was a major job-to-be-done; Joe Nocera explained in his 1994 book, A Piece of the Action:

Fresno’s shop owners knew for a fact that, on the day the program began, some 60,000 people would be holding BankAmericards. That was a powerful number, and it had its intended effect. Merchants began to sign on. Not the big merchants, like Sears, which had its own proprietary credit card and saw the bank’s entry into the credit card business as a form of poaching. Rather, it was the smaller merchants who first came around. Larkin remembers visiting a drug store in Bakersfield, hoping to persuade its owner to accept BankAmericard. “When I explained the concept of our credit card,” he says, “the man almost knelt down and kissed my feet. ‘You’ll be the savior of my business,’ he said. We went into his back office,” Larkin continues. “He had three girls working on Burroughs bookkeeping machines, each handling 1,000 to 1,500 accounts. I looked at the size of the accounts: $4.58. $12.82. And he was sending out monthly bills on these accounts. Then the customers paid him maybe three or four months later. Think of what this man was spending on postage, labor, envelopes, stationery! His accounts receivables were dragging him under.”

A store owner who accepted the credit card was, in effect, handing his back office headaches over to the Bank of America. The bank would guarantee him payment — within days instead of months — and would take over the role of collecting from the customers. As for the bank, in addition to taking its 6 percent cut, the card was a way to get its hooks into businessmen who were not yet Bank of America customers.

It’s easy to forget just how many things a business that takes credit cards does not need to do: it does not need to extend credit, it does not need to collect payment, it does not need to handle excess amounts of cash. It does not, as Nocera noted, need to have much back office functionality at all. Instead banks provide the credit, Visa provides the infrastructure, and merchants pay around 3% of their sales.

Visa’s Network

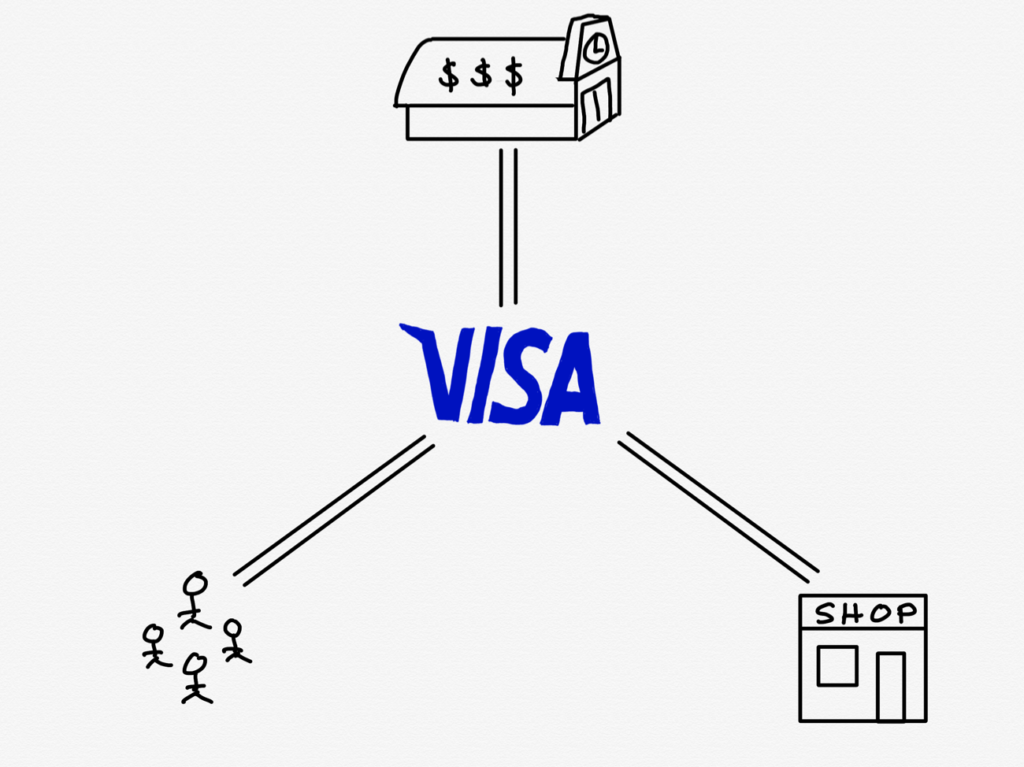

Not that merchants have much choice in the matter these days. Credit cards are perhaps the best possible example of the power of a multi-sided network; Visa sits in the middle of banks, consumers, and merchants:

Everyone benefits from each other:

Customers and Banks:

- Customers want to have always-available credit

- Banks want to provide credit with high fees and interest rates

Customers and Merchants:

- Customers want to have a card that works everywhere

- Merchants want to be able to accept payments from anyone

Merchants and Banks:

- Merchants want to be able to sell on credit while still getting their money immediately

- Banks want to collect a fee on every purchase in exchange for managing credit and pooling risk

Visa and Mastercard, the other major credit card network,1 sit in the middle of each of these relationships, across billions of customers, millions of merchants, and thousands of banks, collecting a network fee — on top of the interchange fee paid to banks — on every purchase (about 0.05%). The total revenue collected — $20.6 billion in 2018 — is rather small, particularly relative to Visa’s market cap of $420 billion, but that multiple is a testament to just how durable Visa’s position is in the network it created.

Plaid’s Network

There are some obvious parallels to be drawn between Visa’s network, particularly in its earliest days, and Plaid, the fintech startup Visa acquired yesterday. From the Wall Street Journal:

Visa Inc. said Monday it would buy Plaid Inc. for $5.3 billion, as part of an effort by the card giant to tap into consumers’ growing use of financial-technology apps and noncard payments. More consumers over the past decade have been using financial-services apps to manage their savings and spending, and Plaid sits in the middle of those relationships, providing software that gives the apps access to financial accounts. Venmo, PayPal Holdings Inc.’s money-transfer service, is one of privately held Plaid’s biggest customers.

Visa is the largest U.S. card network, handling $3.4 trillion of credit, debit and prepaid-card transactions in the first nine months of 2019, according to the Nilson Report. Its clients are largely comprised of banks that issue credit and debit cards, but the company is looking to expand its presence in the burgeoning field of electronic payments, where trillions of dollars are sent by wire transfer or between bank accounts globally each year.

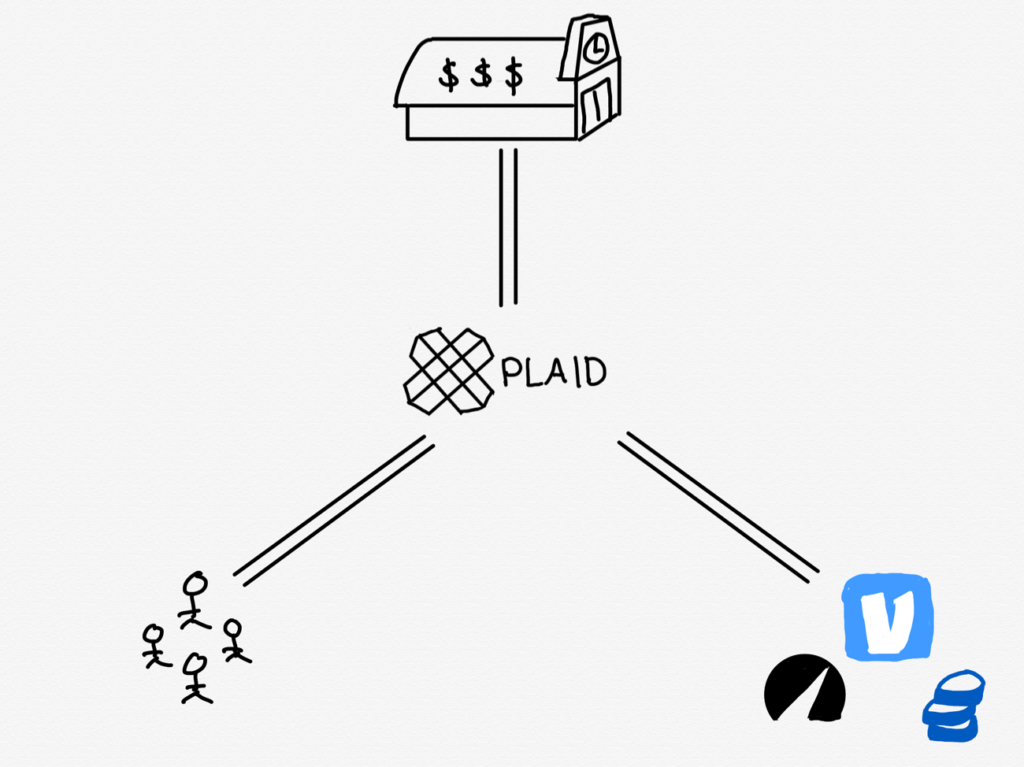

Plaid has its own three-sided network, but it operates a bit differently than Visa’s:

The benefits to some parts of the network are more obvious than others:

- Developers are able to immediately connect to their customers’ bank accounts without having to implement custom integrations with thousands of banks or waiting several days for traditional verification methods (making two deposits of less than a dollar and having the customer report how much).

- Consumers are able to use new fin tech apps like Venmo immediately, without having to wait several days.

- Banks…well this is where it gets messy.

Plaid’s Product

To understand how the banks fit in this network it is important to understand what exactly Plaid does. Many banks in the U.S. do not have APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) that offer a programmatic means of accessing a particular account; those that do are not consistent with each other in either implementation or in features. Plaid gets around this by effectively acting as a deputy for consumers: the latter give Plaid their username and password for their bank account, and Plaid utilizes that to basically log in to a bank’s website on the user’s behalf.

If this sounds a bit shady, well, it kind of is! Bank login information is among the most sensitive credentials consumers have, and apparently one in four people in the U.S. with a bank account have shared those credentials with Plaid. Nearly all did so without knowing any better; here, for example, is the interface Betterment offers when you try and add a bank account:

That is not an interface for Chase; it is Plaid,2 effectively training end users to enter their bank credentials in an app and/or on a site that is not their bank! Oh, and because this is very much a hack, Plaid fails between 5 and 10 percent of the time.

Developers, it should be noted, aren’t particularly bothered by this: in fact, they are paying Plaid for every successful log-in. Users, meanwhile, are likely unaware about just how much access and data they are giving away, but at the same time, have a real desire to access new financial services that require a connection to their bank account. The big problem is that the banks aren’t too sure if they want to participate.

The reticence is understandable. There is, for example, the fact that many banks’ technical infrastructure is ancient and built around assumptions that did not include APIs for 3rd-parties. More importantly, though, is the power of inertia: as long as it is hard to move money around, the more likely it is that that money will stay in the bank, collecting minuscule interest; or, if customers need value-added services, the path of lowest resistance will be simply getting them from their bank.

An API-based world could change this dramatically: suddenly consumers could commission robo-advisors to move their cash to whoever is offering the best rates, or to automatically refinance debt. Value-added services from multiple vendors would be equally easy to access, meaning they would have to compete on price or terms. In other words, much like the open Internet, banks fear that profits will be rapidly transformed into consumer benefit.

Jobs for Banks

This is where Visa can potentially make a difference and, by extension, pay for this acquisition. $5.3 billion is very steep — around 50x revenue — and Plaid’s business model is not particularly attractive: the company makes the majority of its money when users connect their bank accounts, which for most applications is a one-time event; contrast that to Visa’s credit card network, which earns a fee on every single transaction.

UPDATE: Plaid makes money every time a user accesses their account for a transaction; for example, every time you pay someone in Venmo. The company says that revenue from these recurring transactions now exceeds revenue earned from bank verification.

What Visa needs to do is figure out what jobs it can do for banks that makes it worthwhile for them to build out the necessary APIs. The most obvious one is security; as a U.S. Treasury Report on Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation noted:

The practice of using login credentials for screen-scraping poses significant security risks, which have been recognized for nearly two decades. Screen-scraping increases cybersecurity and fraud risks as consumers provide their login credentials to access fintech applications. During outreach meetings with Treasury, there was universal agreement among financial services companies, data aggregators, consumer fintech application providers, consumer advocates, and regulators that the sharing of login credentials constitutes a highly risky practice.

A second job Visa can do is being the devil banks know; that same Treasury report highlighted the fact that the United Kingdom and European Union have initiatives requiring API access to bank accounts, but recommended a private solution. Visa, after this acquisition, is well-placed to leverage Plaid’s widespread use in fintech application and its relationship with banks to come up with a standard that will likely be more favorable to the banks than one imposed by the government.

What is most necessary, though, is selling banks on the idea that they no longer need the equivalent of three people working on bookkeeping machines; hand over those customer service headaches to companies that will specialize in them, over rails Visa will provide.

Visa’s Optionality

This hints at the best case scenario for Visa from this acquisition: a new financial network, with Visa at its center, transforming the consumer financial services industry just as the credit card transformed the consumer retail industry. If that happens, it’s not out of the question that such a network will be so superior to today’s means of moving financial information and data that the company will be able to charge an ongoing toll, instead of simply a set-up fee (and, perhaps, share it with the banks).

The worst case scenario, meanwhile, will see Plaid’s creaky approach deliver barely good enough service to fintech applications in the U.S., with nothing near the reliability or profitability of Visa’s credit card network. Which, from Visa’s perspective, is not a problem either!

Visa will also be able to help Plaid expand internationally, including to more favorable markets like the U.K. and E.U. At first glance, open banking might seem to be a problem for Plaid, but the truth is that screen-scraping is not a long-term solution, and developers will still prefer to use one well-built API that abstracts away thousands of financial institutions instead of re-inventing the integration wheel.

And, most importantly from Visa’s perspective, the credit card business is not going anywhere — if anything, it’s getting stronger. Companies like Stripe are making credit cards more useful in more places, while Apple is making it even easier to use credit cards both online and offline. It is tempting to look at how payments work in countries like China, but that ignores the path dependency of one market using cash until recently, and the other receiving unsolicited Bank Americards 61 years ago. Once a job is done — and credit cards do their jobs very well — it takes a 10x improvement to get users to switch, and, in a three-sided network, that 10x is 10^3.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

- American Express and Discover, the other major credit card companies, integrate the banking and network components; they still facilitate a network between merchants and consumers

- Well technically Quovo, which Plaid bought last year in a smart move to consolidate its position